Biography of Jed for Students

*This article is copyrighted but may be used or copied by any student or serious scholar.

As the Europeans left their homelands to seek a new life across the Atlantic Ocean, they faced many hardships in the unexplored lands of America. At first, these immigrants mainly inhabited the eastern coastal areas and did not venture into the unknown lands in the West controlled by Native Americans. Eventually, though, an increasing number of settlers migrated west, and a few became heroes and earned a place in history. These were men such as Daniel Boone, Lewis and Clark, Jim Bridger, and Kit Carson. An overlooked, but very important early explorer was our Jedediah Strong Smith, who at the early age of 32 was killed before he could publish his journals and maps. For many years his story remained in the shadows of history.

Born in Jericho, New York (renamed Bainbridge), on January 6, 1799, Jed Smith grew up hunting and trapping in the forests of New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. He also learned to read and write, skills that not all mastered on the American frontier. Jed not only read the Bible, but he also read about the Lewis and Clark expedition. He dreamed about blazing new trails and exploring the unmapped lands of the West.

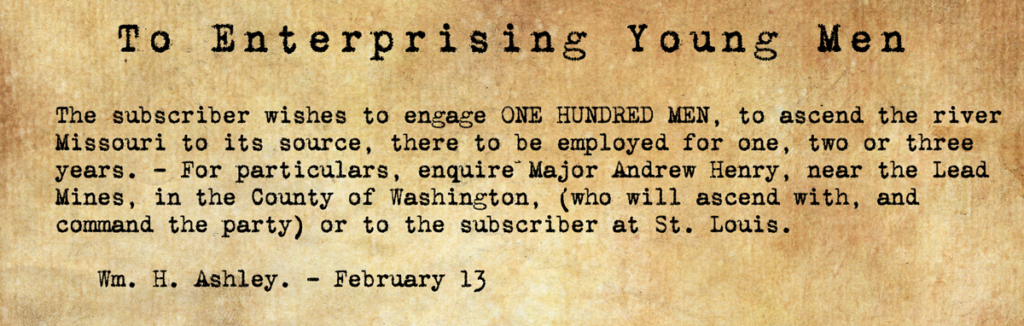

In 1822 Jed’s dreams became reality thanks to a newspaper advertisement that appeared in St. Louis. William Ashley was hiring one hundred men to go up the Missouri River to trap beaver in the new territory. Jed realized this was an opportunity he couldn’t pass up: it would not only fulfill his desire to explore but also produce a good income he could share with his struggling family in Ohio. Experienced in frontier skills, this 6-foot, 3-inch, powerfully built twenty-three-year-old was just the person Ashley needed. He hired Jed on the spot to be a hunter for his party.

On the morning of May 8, 1822, Jed and the rest of the Ashley men loaded supplies on the keelboat Enterprise and started their journey up the Missouri River. Unfortunately, three hundred miles upriver the boat sank, and the men had to wait several weeks for another boat to arrive before they could continue their trip.

The boat was pulled upstream against the current by a long rope called a cordelle. The men walked on the bank, waded along the shore, all the time dragging the boat. Sometimes oars or poles could also be used to move the boat along. Or if the wind was strong enough, a sail could be raised that would help provide power. It was hard work, and progress was slow. The only advantage was that they did not have to fight Indians; the tribes along the river let them pass without interference, in peace. Because of his skill as a hunter, Jed spent most of his time ashore bringing fresh meat to the camp for the hungry men.

It was October when they finally arrived at their small fort on the Yellowstone River above the Missouri. Ashley divided the men into small groups to trap the valuable beaver pelts. He then returned to St. Louis for more supplies. Jed’s party went farther up the Missouri River and set up camp on the Musselshell River (in today’s Montana).

During this first winter in the Rockies, the need for additional horses arose after several of their scattered trapping parties were attacked by unfriendly Blackfoot Indians. In June Jed was sent downriver to find Ashley and tell him about the missing horses. He met Ashley near the Arikara Indian village, which was a fortunate meeting place to acquire horses. However, due to the recent hostilities of this tribe, Ashley and his men had to take special precautions. The Arikara had extra horses and were willing to trade. Jed and a few men spent the night on the riverbank to keep a close watch on the newly purchased horses, but just before dawn the Indians began shooting at the trappers from inside the walled village. Soon Jed and the other men had only their dead horses for cover. To escape this dangerous situation, Jed and the party dove into the river and swam to safety. In the battle, twelve men were killed, and ten were wounded.

When Ashley asked for a volunteer to go to the fort on the Yellowstone for help, Jed went and soon returned with reinforcements. While Jed was gone, Ashley rounded up a party of Sioux warriors and a US Army troop. Together, they formed a force large enough to defeat the Arikara, who agreed to repay Ashley for the horses and supplies the trappers had lost. However, during the night the Arikara left their village and escaped without paying anything.

Before Ashley returned to St. Louis to obtain more supplies, he appointed Jed to be captain as a reward for his leadership, bravery, skill, and reliability in the conflict with the Arikara. The new captain led his men deeper into the Rockies in search of the wealth beaver pelts would bring to the company. Near the Cheyenne River, as the men were pushing their way through the thick brush, a huge grizzly bear attacked. The grizzly, the most ferocious and dangerous animal in the West, could break a horse’s back with one swipe of its giant paw. It was on Jed in an instant. The trappers watched in horror as their captain fought the bear. Before Jed could fire his gun, the animal clawed him. It ripped open his side, breaking several ribs, and then the bear’s large jaws closed on his head. The grizzly suddenly bolted back into the brush. The men gathered around their leader, sickened by the sight of blood that covered his body. Jed’s left ear dangled from his head. His scalp had been torn and his forehead gashed by the teeth of the bear. He fought to keep his wits about him. Then he ordered his companions to get water, clean his wounds, and sew up the cuts on his head. The trappers also bound up his broken ribs and repaired his ear as well as they could sew. Ten days later Jed was out checking his traps. His wounds healed quickly, but he had terrible scars for the rest of his life.

That winter Jedediah took his men into Wyoming, where they stayed with a friendly band of Absaroka (Crows). They told Jed’s party that to the southwest there was a gap in the mountains that would allow them to cross easily. Jed knew that such a pass would make east-west travel much easier, especially by wagon. By February they were on their way to find it. The party went without food for several days because there were few animals to hunt in the deep snow. For over two weeks, their only water came from melting snow.

Their southwest journey finally took them to a broad, level pass. Jed made a map and added notes so that he could find it again. This discovery would be known in the history of the West as South Pass, and it would become the single most important land feature in the transcontinental movement of the United States to the Pacific Coast. The gap would serve as the passage through the Rockies for the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails.

That spring Jed and his men trapped streams no white man had seen and made a huge catch of furs. In June Jed returned to the fort to report their discoveries to Ashley and to get fresh supplies. At this time his career would change again. Ashley’s partner, Andrew Henry, was quitting the fur business, and Jed was asked to take his place. Within a year Ashley also quit and sold the company to Jed and two other men, David Jackson and William Sublette. The new partners decided to split up the duties of running the company into three jobs. Jed was to search for new beaver streams in the West. In August 1826 Jed led seventeen trappers on a trip that would last over two years. This trip would open California and Oregon to the fur trade and also to future American pioneers.

The party left from the rendezvous in Cache Valley, riding southwest into the valley of Great Salt Lake, making their way south through deep canyons, towering peaks, and rushing streams and rivers. They crossed the Colorado River near the southern tip of what is now Nevada. Here they met a tribe of Mojave Indians and rested with them along the river for several days. From the Mojave they bought food, some horses, and learned about the dry region, the Mojave Desert, which lay westward. By the time they reached the mountain ridge on the border of this desert, the men were thirsty and blistered. On the other side of the ridge, however, was the San Bernardino Valley. They were the first white men to travel from the United States to California overland!

In 1826 California was part of Mexico, and its government did not want Americans to enter on an overland route. The Mexicans were afraid they would lose their territory if too many foreigners moved there. They did not have enough soldiers and money to keep the Mexican government in control. So, Jed’s arrival was not a cause for celebration. The Mexican governor thought Jed was an American spy and told him he had to leave the way he had come in and not to go north.

Jedediah did not want to face the desert hardships again. He wanted to search for beaver streams to the north. Complying with the governor’s orders, Jed and his men did depart the way they had entered, but upon passing through the San Gabriel Mountains, they resumed their journey north along the backside of this range. At this time, most felt that Mexican California was a territory narrowly defined as “the settled belt along the coastal plain”; therefore, Jed felt free to proceed with his plan to go up through and along the east side of the Central Valley. Although winter came on, the weather in California was mild, and Jed’s party trapped as they moved northward. In the spring they had a good catch of fur and hoped to cross the Sierra Nevada and return to their rendezvous located east of Great Salt Lake at Bear Lake. High peaks and heavy snows forced the party to continue north.

Upon reaching the vicinity of the present-day capital of California, Sacramento, they attempted to cross the Sierra Nevada via the American River but with disastrous results. Losing horses and equipment, and fearing for the life of his men, Jedediah returned to the valley floor and headed back to the Stanislaus River, which he had previously visited. There he left most of his men in safe camp. Taking only two men, he headed east across the mountains toward the unknown lands of Nevada. The snow was still very deep, and it was very cold. On certain days they could move only two miles through the deep snow. Upon crossing, they had to face more deserts, but there was no choice. In hot and dry weather conditions, they traveled many miles over sandy hills with few plants and fewer waterholes. One hot miserable day followed the next. For six hundred miles the men stumbled through the desert wasteland. They ran out of food and grew weak from hunger, eating their horses as they fell and perished on the desert floor. One of the men gave up, too weak to go any farther. Jed and the other man struggled on another two miles. Finding water, they returned to revive their companion. All three travelers eventually came upon Great Salt Lake, and in early July 1827 they reached the camp and rendezvous site along the shore of the Bear Lake.

After ten days rest, Jed began his return trip to California with eighteen men and the needed supplies. He decided to follow the original southern route and reached the Colorado River and the Mojave village. Unfortunately, the Mojave were now hostile—though they hid their hostility by acting friendly. Unknown to Jed, other trappers out of Taos (in present-day New Mexico) had previously visited this tribe, caused problems, and killed tribal members. Consequently, the Mojave were intent on revenge. After Jed and some of his men reached the California side of the river, they realized that their companions had come under attack. Greatly outnumbered, nine trappers were quickly clubbed or stabbed to death by the angry Mojave. Ten survivors gathered what supplies they could and headed west.

Without horses or water and very little food, the journey was again a struggle. By traveling at night, Jed could keep his men out of the killing sun and keep a watchful eye for any Mojave that might be following. Ten tormenting days later they again found themselves in the San Bernardino Valley. After resting, they headed north, following their previous route along the east side of the Central Valley to the encampment on the Stanislaus River, where some of Jed’s men had remained.

Because the supplies had been lost, Jed took a few men and headed to Mission San Jose to replenish some of those needed items. Upon arrival, the party was immediately imprisoned, and Jed was sent to Monterey, where he was quickly arrested by suspicious Mexican officials. The same Mexican governor Jed had dealt with in San Diego was now residing in Monterey. Jed again had to confront this indecisive government official. After much futile discourse over a three-month period, masters of several vessels in port, along with an American resident living in Monterey, devised a plan that released the governor of all responsibility. A bond was issued that guaranteed the good conduct and expedient departure of Jed and his men from Mexican territory. Selling his beaver pelts and purchasing supplies, horses, and mules, which he knew would sell quite well at the upcoming rendezvous, Jedediah slipped away to the Great Central Valley in a northerly direction—the quickest way he knew to make his escape.

He headed for the Buenaventura (Sacramento) River. All current maps showed that this river turned to the east above what is now Sacramento and pointed toward Great Salt Lake. Driving his valuable horse and mule herd up the Buenaventura became quite difficult due to the spring snow melt that had flooded the valley. Reaching the north end of the (Sacramento) valley, he realized that this river would not swing east and that it would be impossible to cross the high snowcapped mountains blocking his way. On observing a gap in the mountains to his west, Jed’s only alternative was to head to the coast in hopes of traveling up it to the Columbia River and back to the Rocky Mountains. With much difficulty and the loss of several horses and mules, Jed’s party reached the Pacific Coast and began to move northward.

The coast was rugged, wild, and populated by friendly as well as unfriendly Natives. Up the coast in southern Oregon, the party encountered a warlike tribe near the Umpqua River. When a member of the Kelawatset tribe walked off with an ax from the expedition (a necessary tool used to cut through the thick coastal vegetation), the thief was apprehended and held until the ax was returned. Several days later a chief of this tribe mounted one of the trapper’s horses without permission and refused to dismount. The next day, while Jed and two men were off scouting for a route north, the Kelawatset, having sworn revenge for the insults inflicted on them, raided the camp. They killed all but one man who cheated death by his brute strength and fast running. The Indians took all of the horses, supplies, and fur pelts.

Separated, the four survivors struggled over 150 miles north to the British Hudson’s Bay Fur Company post at Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River, arriving one day apart from each other. The United States and Britain had agreed in 1818 that they would both occupy Oregon. The British were not hostile to the American fur traders. Even though they were competitors, they treated the Americans kindly and even agreed to return to the Umpqua River to try to recover the goods taken by the Indians. However, the Hudson’s Bay people recovered only a small portion of the stolen supplies. In the spring Jed and one of his men (the other two remained behind) headed back to the Rocky Mountains. Since many there had given up the party for dead, the sudden appearance of the Jed and his sole companion must have caused a great celebration.

During the next year Jed worked from the Bighorn Basin along the Wind River in Wyoming to the Musselshell River in Montana. The trapping was successful, and Jed decided to retire from the fur business. In 1830 he and his two business partners sold their interest in the company to some trapping companions who had just formed the Rocky Mountain Fur Company and set out for St. Louis with wagons loaded with the furs.

While Jed was in St. Louis, his brothers joined him and wanted to start in the trapping and trading business, but Jed discouraged them because he knew well the dangers and the declining market for beaver pelts. Instead, he encouraged them to participate in the Santa Fe trade, which his old partners were planning to enter. He helped his brothers by setting them up in this new venture, adding several of his own wagons full of trade materials to the caravan. Jed then decided to go along. In mid-April 1831 the wagons departed for Santa Fe. Within a month, they reached a dry stretch of sandy hills and desert called the Cimarron Cutoff.

The travelers were without water for three scorching days, and their animals were dying of thirst. A last desperate effort was made to find water, and Jed was one of those sent out in various directions. He rode south toward the Cimarron River—the last time his brothers and friends would see him.

Later, his brothers discovered his rifle and pistols for sale in Santa Fe where Mexican traders told the tragic story of Jed’s death. While checking out a small water hole along the river, Jed apparently was surrounded by unfriendly Comanche, who had secreted themselves in hopes of procuring buffalo that might come in for a drink. Spooking Jed’s horse, they were able to get off an injurious gunshot to Jed’s shoulder. Still mounted, Jed spun around and got off several deadly shots, one of them at the chief, before the others came in with their long spears and ended Jedediah Smith’s life. Or so the story goes—we do not know the details of Jed’s death with certainty.

Jedediah Smith’s accomplishments during his short nine years as a fur trader and trapper rank him as one of foremost explorers in our nation’s history. He led the first overland party from the East to California. He was the first to cross the Sierra Nevada going east, and the first to traverse the entire length of California overland, up through Oregon to the Columbia River. He rediscovered South Pass in today’s Wyoming and was the first to bring to the public’s attention that wagons could easily use this pass to access the West. Finally, Jed traveled over twice the distance of Lewis and Clark and covered a broader territory on both a southern route and a central route to the West Coast. Unfortunately, Jed died before he could publish his map of the West, but we know that this map influenced other mapmakers and explorers. His journals, not located and published until the twentieth century, now help us to better understand the West—its Native peoples, its geography, its botany and zoology, its politics and its settlement.